Inmates in Ontario jails held at least 50 hunger strikes in 2023. Experts say the true figure could be much higher

Provincial records show at least 50 hunger strikes were held in jails across Ontario last year, but experts say the true figure could be much higher.

The data, obtained through a freedom of information request, is drawn from the number of incident reports filed by staff at provincial adult correctional facilities, where the vast majority of the inmate population was found to be awaiting trial in 2023.

According to the documents, inmates held hunger strikes in every month of 2023. Over half of those actions were held in the central region, with the most (15) taking place at Central East Correctional Centre in Kawartha Lakes, followed by 11 at Ottawa Carleton Detention Centre and five at Maplehurst Correctional Centre in Milton.

Experts say the records make up one of the most detailed portraits of organized action in Ontario provincial jails to date, even if they’re likely incomplete.

“I would venture to say the true number is quite a bit higher,” Dr. Jessica Evans, who teaches criminology at Toronto Metropolitan University, told CTV News Toronto. “There’s not a huge degree of oversight on reporting these kinds of actions or coordination between facilities,” she said.

When reached by CTV News Toronto, the Ministry of the Solicitor General did not respond to a request for further data on hunger strikes in additional years. A spokesperson said that inmates who refuse meals continue to have access to food through the canteens and that facility staff monitor the health of participants.

Dr. Jordan House, an associate professor of labour studies at Brock University, wasn’t surprised to hear inmates had held at least 50 actions in 2023.

“Prisoners have been organizing protests to assert their rights or advance their interests for as long as there have been prisons,” House said. “But this is probably the best data I’ve seen out there yet.”

Still, the reports lack important context, he noted. For example, each document asks for the date and time each action began, the facility where it took place, when it was reported to a regional office, and whether the media was aware of the protest, but lacks entries to list the number of inmates involved, the length of each action, or the demands that sparked the protest.

The issue of transparency extends well beyond reporting protests, House added.

“It’s notoriously difficult to get data out of corrections, both provincially and federally,” House said. “It takes a tremendous amount of effort for just a small amount of accountability from these public institutions.”

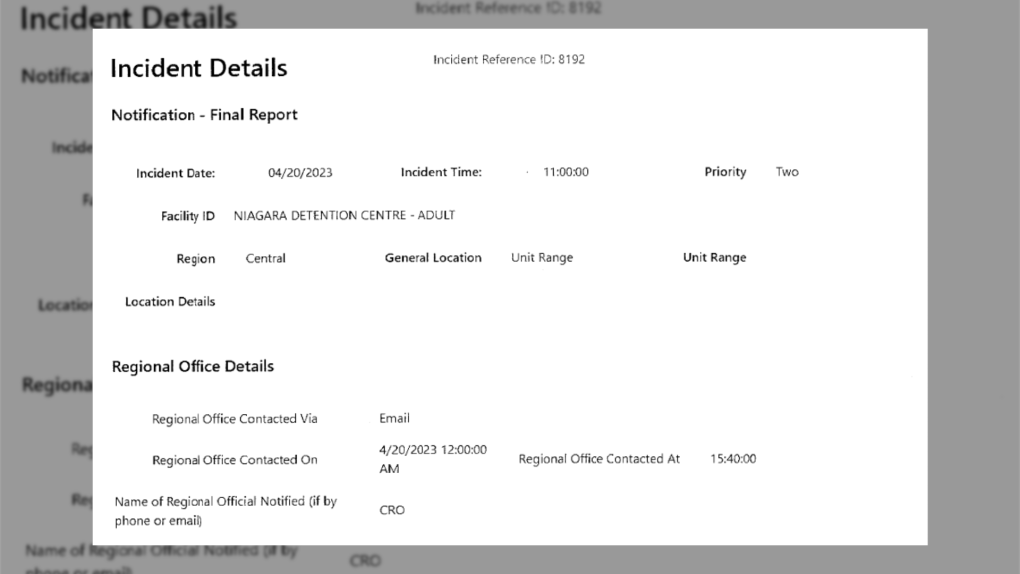

One of the 50 P2 incident reports obtained by CTV News Toronto.

One of the 50 P2 incident reports obtained by CTV News Toronto.

According to Ontario resident and former inmate James Ruston, peaceful forms of prisoner protest often don’t garner as much public attention as protests deemed violent.

“There’s a real lack of information out there on carceral struggles,” Ruston told CTV News Toronto. Ruston spent the better part of two decades behind bars after he was handed a life sentence at the age of 17. “Usually only the sensationalized incidents, the rioting or violence, get a great deal of attention,” he said.

Even in the absence of public data, both House and Evans, who co-authored a report on the topic, said anecdotal evidence suggests organized action is on the rise in Ontario correctional facilities, in part in response to substandard conditions and near-constant lockdowns.

At Ottawa Carleton Detention Centre (OCDC), for example, where Evans said strikes have become a regular occurrence, “the conditions have been quite bad for some time,” she said.

The Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre, opened is 1972, is located on Innes Rd. in Gloucester and houses both male and female offenders. (Chris Scott/CTV Ottawa)

The Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre, opened is 1972, is located on Innes Rd. in Gloucester and houses both male and female offenders. (Chris Scott/CTV Ottawa)

Collective action is difficult in provincial jails, where inmates generally have much shorter stays and, in turn, there is a lack of programming offered, Evans continued.

“Everything about a jail, detention centre, correction facility is designed to militate against collective action,” the professor said.

An overcomplicated system to file formal grievances could also be a factor, Ruston said. As it stands, if prisoners have a grievance, they can file a complaint, he explained. The process, however, involves raising complaints to multiple levels of management before it can reach the warden and beyond that, the only remaining avenue is the courts.

“It’s a means of exhausting the prisoners’ energy,” he said.

To better understand the demands and needs of prisoners, Ruston says the barriers between the public and incarcerated population need to be broken down.

“By increasing opportunities to interact, it … elevates [prisoners’] sense of personal value, of what they can then offer back to the community,” he continued. In recent years, he said he’s considered compiling a public log of prisoner grievances using what is obtainable through information requests.

In lieu of further transparency between inmates and the public, Ruston points those looking to support prisoner populations to organizations like the Toronto Prisoners Rights Project and the John Howard and Elizabeth Fry societies.

“They’re doing great work in breaking down the divide.”

View original article here Source